Underground

South African Underground Comix

The comic subgenre underground comix was the result of a decades-long struggle between censorship and the recognition of legitimate art.

In the first half of the 20th century, the superheroes of the two main publishers, Marvel and DC, and the funny animals of the Walt Disney Company dominated the comic landscape in the USA. These comics followed the classic dichotomous narrative of good and evil, thereby conveying a kind of morality to their primarily young readership. Later, horror and crime comics were increasingly aimed at an adult readership. As the genre has grown in popularity, the depictions of violence came under strong criticism. As a result, comic book publishers established the Comics Code Authority (CCA) in 1954, which banned any depiction of nudity, horror, bloodshed and criminal atrocities in comics.[40]

Up until then, the so-called Tijuana Bibles[41] comics, which contained violence and pornography, had been unlawfully distributed (illegal also because of repeated copyright infringement); the censorship by the CCA brought about a wave of production of illegal comics. The new genre took the name of Comix, (sounding the same as Comics; the x is written out, which also refers to the explicit content). In addition to the publications of underground comix in magazines, satirical and adult comics proliferated in college humour magazines; They were sold under the table in music stores and headshops[42] , and so comix soon became a staple of the counter culture[43] and punk scene of the 1960s and 1970s.

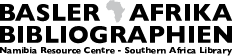

Ill. 1: One of Kannemeyer’s latest works: My Nelson Mandela deals with his eye-opening experience in Europe. Joe Dog: My Nelson Mandela. In: Kannemeyer, Anton: Pappa in Doubt. Auckland Park 2015, p. 7.

It turned out that 1990s South Africa provided a perfect breeding ground for a satirical and socially-critical comic genre, as well. The South African underground comix Bitterkomix has been published and co-authored by Anton Kannemeyer and Conrad Botes since 1992. They are the children of a generation of white South Africans, whose lifestyle and support of the apartheid regime are the primary target of Bitterkomix. Both Anton Kannemeyer aka Joe Dog and Conrad Botes aka Konradski grew up in typical white South African cities[44] – isolated from the world around them and dominated by the dogmatic worldview of the Dutch Reformed Church. Education and schooling were repressive and authoritarian, marked by corporal punishment, moralisation, sexual oppression and various taboos.

Only during their joint studies in fine arts at the University of Stellenbosch (as well as during other periods abroad) did the authors come to recognize the damage caused by apartheid in their native land, concomitantly becoming aware of problems within their family environment as well as hypocrisies in the social values and living practices of the Boers.[45] The aim was to confront, to shock, and ultimately to create an uproar in the conservative South African society. The objects of their anarchic fury are above all the religious value system, social ideologies, the family hierarchy as well as the ossified conservativism of the school system. Self-criticism is a striking component, surfacing especially in the autobiographical and self-reflexive elements of the Bitterkomix.

Kannemeyer repeatedly uses the Ligne-claire style developed by the Tintin illustrator Hergé. The strong contrast of black and white and the straightforward divisions of space are well suited to visually reflect the apartheid era. In addition, the Ligne-claire style allows the use of iconographically exaggerated figures that contrast with the naturalistic background.

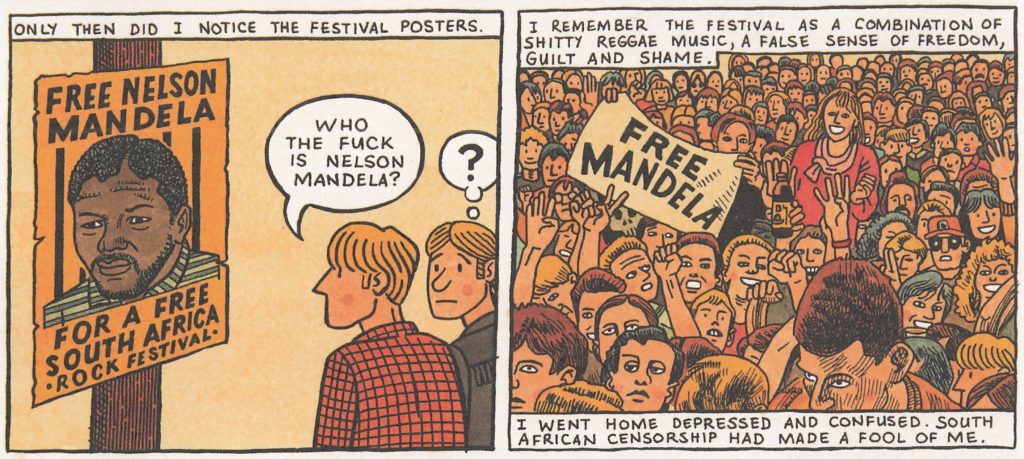

Ill. 2: The Cover of Bitterkomix 17 alludes to the student protests at South African Universities in 2016. Joe Dog: 16 Februarie 2016. In: Kannemeyer, Anton / Botes, Conrad (eds.): Bittercomix 17, Cape Town 2016, cover.

The cover of the latest issue Bitterkomix 17 shows a joyful, drunken group of black South African students dancing around a bonfire into which copies of Bitterkomix are thrown; a painting shows a white South African crying in the face of the destruction. The cover alludes to the student protests of 2015 and 2016 – under the rubric #FeesMustFall – over the increase in tuition fees and the lack of government subsidies in education. There had been large-scale incineration of paintings belonging to the University of Cape Town (UCT), which students perceived as the embodiment of colonialism. The painting with the crying white man on the cover, according to Anton Kannemeyer, depicts those archetypal colonialists. Immortalized as art, they are consigned to oblivion with the burning of the artworks together with all white patriarchal structures/systems. Kannemeyer works consciously with irony here: In contrast to the events at UCT, the cover of Bitterkomix 17 not only shows the burning of paintings by South African white colonial artists, but also of anti-apartheid art such as Bitterkomix. Kannemeyer thus denounces not only the aimless destruction of art by the students, but also the subsequent censorship of further works of art by the UCT itself.[46]

Seen in this light, the creators of Bitterkomix have changed their focus. While during the 1990s the white apartheid structures were still the target of satire, today it is the public institutions in general and the controversial ANC government in particular that are critically scrutinized.

YouTube Playlist