Images of Africa

Africa, as seen through western eyes

Although the heyday of European colonialism in Africa has been over for more than a hundred years, its influence endures on various levels to this day. Only in the ‘70s and ‘80s did the colonial stereotypes begin to come into question. Though many are not aware of it, this process has not yet been completed, as many outdated patterns of thought still shape our perception. For example, an African village was set up at the Augsburg Zoo in 2005, in which Africans were exhibited along with the animals. Several critical voices had pointed out in advance that this African village was in the traditional line of “Völkerschauen” (human zoos). The staging and exhibition of Africans for the European view took place also through images, whether in photography, advertising or comics. These representations were very often imbued with racist thinking and numerous related stereotypes. In the nineteenth century, these stereotypes were reinforced by a pseudo-scientific racial doctrine.

Ill. 1: “Natives” as subject of photography: this illustration from a 1950s German travel brochure (Reisen in Süd-Afrika) stages the divide between the white and the three African women on many levels. Nederveen Pieterse, Jan: White on Black. New Haven / London 1992, p. 105.

The presentation and representation of the African continent in Europe was informed by concepts such as exoticism and adventure, and peoples living in pristine nature. The ambivalence between this idea and the European claim to civilise and bring progress[1] was expressed in numerous representations of Africans. On the one hand, shown half-naked and often with traditional jewellery, their inferiority relative to the self-image of the Europeans was emphasized (s. Abb. 1). On the other hand, in such romanticized images, a “critique of the alienation processes in ‘modern’ industrialised Europe” was expressed by Europeans themselves.[2] It was only through establishing the “savagery” of the others that their own civilised behaviour could be perceived at all.[3] Nevertheless, in colonial and missionary photography, resistance by the Africans to their dehumanization can sometimes be recognized, since they have their specific facial expressions and gestures.[4]

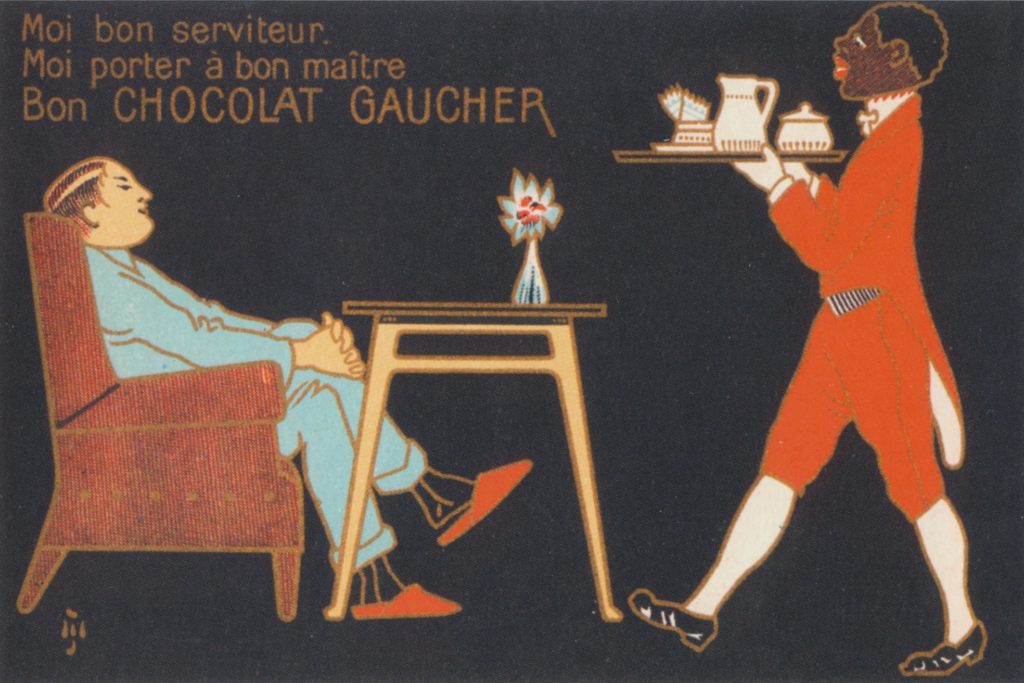

In the heyday of imperialism[5] (the late 19th and early twentieth century), the European – and American – advertising made dark-skinned people a ubiquitous motif. Products which had become affordable for Europeans through slave labour, such as sugar, rum, tobacco, cocoa, coffee and tropical fruits, were especially often advertised with stereotyped Africans.[6] By stereotyped should be understood: painted or drawn in a caricature, with skin hues very dark to deep black, with exaggerated thick lips and frizzy hair, semi-nude and wearing pseudo-traditional clothing.[7]

Ill. 2: Advertisement for Chocolat Gaucher from ca. 1912: the typical colonial products are delivered to the “white master” by a “black servant.” Zeller, Joachim: Weisse Blicke – Schwarze Körper. Erfurt 2010, p. 168.

A similar image of Africa, for example, shows Hergé’s Tintin au Congo (1930, Tintin in the Congo[8])—from the Belgian series The Adventures of Tintin. The African people speak laughably incorrect; they are drawn with oversized lips; they are submissive, gullible and technically ignorant; and dependent in almost all matters on the help of the European visitors. They appear either half-naked or wearing inappropriate European clothing such as parts of uniforms or fur coats. Tim and Struppi were cartoon characters, with whom whole generations of children and adolescents grew up. These figures have influential views on issues such as dealing with non-European peoples. This influence was increasingly discussed in the public forum, especially from the 1970s onwards.

The reactions to criticism of widely used and popular (children’s) books and comics were generally defensive. The discussion over Tintin in the Congo evolved in a similar vein: although Ralf Keiser, the programme director at Carlsen comics, stated at a public event that he would no longer accept such a booklet today, this statement had no follow-up; the comic, “for licence-related reasons”, as the publishers insisted, still appears without a preface or epilogue.[9] In England and the USA, however, the comic remained banned until 2005, and is now only available outside the children’s book department and supplied with a warning and a preface. In Belgium, a lawsuit was filed in 2007, citing an anti-racism law, to halt the sale of Tintin in the Congo; The lawsuit, however, was rejected 2012 by two courts on the grounds that the comic was an expression of its time and could not be judged by today’s standards.[10]

Colonial and racist perceptions and representations of Africans are still very much alive in the western world. It is therefore necessary to take a critical look at such patterns of representation – beyond their own narrow horizons.

YouTube Playlist