Educational Comics

Comics with an educational focus

Comics can do more than entertain; this medium is often used to transmit content to a broad target audience. Educational or non-fictional comics are a tool to facilitate learning. Educational comics are, for example, teaching comics that attempt to teach about a content or so-called awareness comics that want to raise awareness of a particular topic. A historical comic, e.g., is a teaching comic dealing with a specific content. Another group is instruction comics (e.g. Will Eisner’s P*S magazine), which provide specific instructions, for example, for repairing a motor.

Instruction comics and educational comics

Teaching and education comics had an upswing in Africa in the second half of the 20th century. For various reasons, non-fiction comics or educational comics are central to research into the comic culture on the African continent and for the comic culture itself. The medium of comics has the advantage of reaching people with low levels of education and educating them in a simple way about complex issues.

Publication groups were also formed with the specific educational goal of reaching the poorly educated through comics.[11] One of these groups is the SACHED Trust in South Africa and the Legal Assistance Centre in Namibia. A number of NGOs as well as UNICEF published educational comics for an African audience. A notable artists’ collective is the South African Storyteller Group, which was particularly active between 1991 and 1996.[12]

The Storyteller Group

The Storyteller Group has published educational comics focusing on various topics[13], with a particular interest in the presentation of possibilities for a course of action. Instead of pushing an explicitly political agenda, cooperation is presented as a principal means of improving one’s own situation.

Thematically, the comics differed according to the orientations of the respective clients: The Storyteller Group, for example, was commissioned by the Soweto Civic Association to bring out a comic to educate township residents about rent and services. To help protect employees in troubled areas, the International Red Cross funded a comic highlighting the organization’s neutrality.[14] The Storyteller Group, because it wanted to make its comics available free of charge to a large and sometimes illiterate readership, was financially dependent on NGOs and government agencies; these, in turn, defined the topics of the individual comics. This business model made it difficult to determine exact figures on distribution and readership.[15]

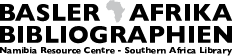

Ill. 1: The last page of the comic informs about the birth registration process at the Ministry of Home Affairs & Immigration in Namibia. Beninger, Christina: How to Register the Birth of Your Child. Windhoek 2011, n. pag.

The Legal Assistance Centre (LAC)

The LAC is a unique organization in Namibia, founded in 1988 with the aim of protecting the rights of all Namibians. In the field(s) of educational and awareness-comics, there are several comics that have been specifically published by the LAC for these purposes.[16] The style of the comics is kept very simple, raising the question as to whether these comics have artistic value, or whether they only transfer the information in simple illustrations. However, the use of panels and speech bubbles clearly suggest that these publications are at least formally classified as comics.

Worthy of mention in these productions is the variety of languages (English, Otjiherero, Khoekhoegowab, Afrikaans, Rukwangali, Oshiwambo, Oshindonga), in which the comics were published in order to better reach the multilingual population of Namibia.

Conveying historical content in comics

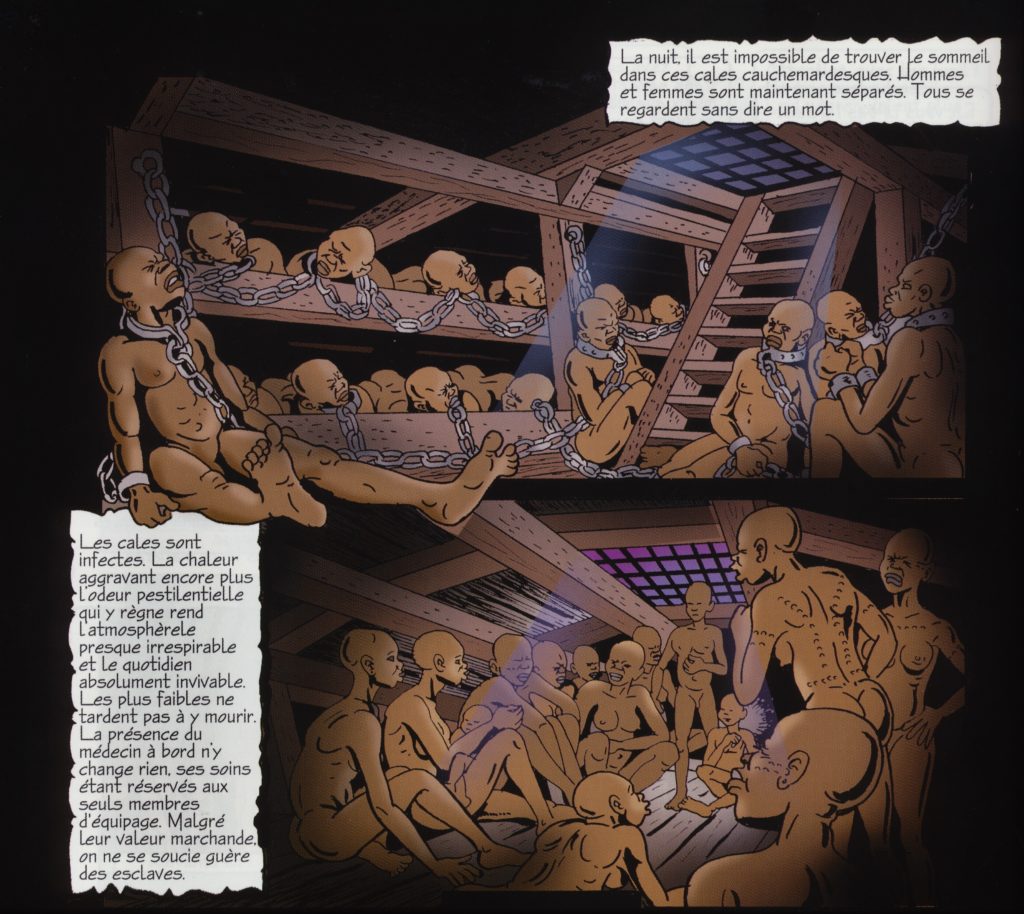

With regard to Africa, complex issues such as slavery and the slave trade are dealt with, for example, in works such as Mémoire de l’esclavage. In comics, history can be visualized without having to dispense with the text level. They can complement history classes as an additional medium and also encourage the reader to deal with history in his free time. They make content more accessible to a young or semi-literate audience.

To create historical authenticity, one can use reproductions of old newspaper clippings. In addition, the integration of facts and figures can support the presentation of historical events (see Joe Sacco’s Palestine).[17]

Ill. 2: The shipping of slaves from Africa to the Americas marks one of the most inhumane ventures during the slave trade. Diantantu, Serge: Mémoire de l’esclavage, Vol. 1. Petit Bourg 2010, p. 42.

Mémoire de l’esclavage

Up to the present, five of the planned seven volumes of Serge Diantantu’s Mémoire de l’esclavage series have been published. The comic tells the story of slavery and the slave trade, stretching from the first contacts of Portuguese military ships with the Congo in the 15th century and shedding light on the transatlantic slave trade into the 17th century. In addition to historical figures – such as the King of the Congo, Mvemba Nzinga (Afonso I), Christopher Columbus and Bartolomé de las Casas –, fictive persons are also introduced. Abducted slaves and indigenous people, both in Africa and in the Americas, are given a face and a name and flesh out the narrative. Voice-over dates and statements, conveyed in boxes rather than speed bubbles as well as statements, help to explain what has happened.

A feeling of authenticity is brought about by various means. On a pictorial level, this is done by depicting period dresses and buildings, on a textual level through historically verifiable facts. The inner cover pages contain thematic maps, which are supplemented by chronologies and graphics. The colourfully designed comic does not stand on its own but is accompanied by other forms of information. The series was published by the small publishing house Caraïbéditions.

YouTube Playlist