Marabi

The Marabi era: South African urbanization, proletarianization and the birth of jazz

In the ‘20s and ‘30s of the last century, a wave of industrialization led to rapid growth in the urban population of South Africa. The African population moved from the country to the city in the hope of better financial prospects, e.g. in the mining industry. As a result, within a very short time a large part of the population was proletarianized and ghettoized.[11] In spite of the fact that official apartheid began only in 1948 with the takeover by the National Party, strong segregation in urban areas was already in place in the South African Union since the Natives Land Act of 1913 (the law which divided the country into “black” and “white” territories). In the growing townships, therefore, an urban working-class culture quickly developed. This stood in a complex relationship to traditional rural cultures as well as to the bourgeois-elitist culture of the black middle class and to the white hegemonic culture.[12]

At the center of this working-class culture were the Shebeens (Irish for illegal pubs). The alcohol trade was banned within the Union for the African population and was therefore only to be encountered at the edge of the cities, in the townships. The Shebeens were mostly operated by women, so-called Shebeen- or Skokiaan-Queens (named after a popular, strong brew of beer). These women continued a brewing tradition, widespread in the countryside, and tried to escape the sexually segregated working system with the sale of alcohol. The Shebeens were characterized by long, often all-weekend parties, as well as by crime, alcohol consumption and music.[13]

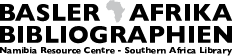

‘American’ gang – Sophiatown 1954, Bob Gosani. Schadeberg, Jürgen: Sof’town Blues. Images from the Black ‘50s. Pinegowrie 1994, p. 38.

This music was Marabi, a concept attributed to a certain music genre, but also standing for an entire era of South African urban culture, which came to a tragic end with the first evictions from inner city black areas. The music style Marabi was characterized by a repeating, ostinato accompaniment, usually in the harmonic pattern I–IV–I64–V, upon which potentially endlessly melodies were improvised. These melodies often consisted of sections of popular pieces of any provenance (folk music, religious music, US jazz, dance music such as Vastrap, etc.) which, like the underlying pattern, could also be repeated at will. Marabi was mostly played on electric organs or pianos, with a percussive accompaniment of cans filled with stones.[14] Unfortunately, no sound samples of early, “pure” Marabi have been preserved (although the genre was always very flexible), since Marabi was never recorded on 78s during its heyday. This is partly because it was an outlaw underground music, but also because recordings were not yet common.[15] The style inspired, however, various genres such as jazz (later Mbaqanga), Jive, Pata pata, and Kwela and is therefore still to be heard in a slightly altered form on recordings of the ‘40s.

Marabi was played in the Shebeens for hours without end, which was intrinsic to its circular form and improvisational nature.[16] The Marabi parties were organized by the Shebeen-Queens to bring in particularly good income from the sale of alcohol on weekends. They quickly became meeting places for the new urban proletariat, venues for trade and exchange[17], and meeting points for criminal gangs and prostitutes.[18] The music had a crucial role in attracting the audience, and the organizers deliberately hired the most talented musicians and ensembles to beat the competition.[19]

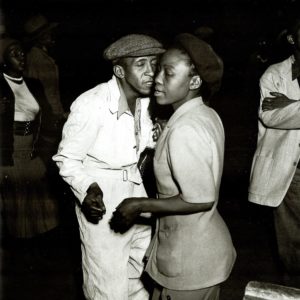

Dancing at a township party – Johannesburg 1952, Jürgen Schadeberg. Schadeberg, Jürgen: Sof’town Blues. Images from the Black ‘50s. Pinegowrie 1994, p. 29.

Within Marabi can be found many of the tensions of South African urban society: A musical style that inherited the circularity of traditional music (which is also found in US jazz and therefore could be seen as a sign of transatlantic African cultural unity), played on Western instruments (organ, piano, clarinets, trumpets, etc.), with improvised melodies and rhythms reflecting the entire spectrum of South African cultures (traditional melodies or melodies from jazz songs, rhythms of dances of the Afrikaans-speaking white or mixed population, etc.), in an urban, proletarian and colonially-suppressed setting, marked by illegality and shadow economies as well as by class identities, hope, and the search for new social circles in an unknown place and last but not least a zest for life and fun.

Thomas Mabiletsa: Zulu Piano Medley, No. 1: Part 1, on: Ballantine, Christopher (comp.): Marabi Nights. Historic Recordings (Accompanying CD), University of KwaZulu-Natal Press 2012. [Original c. 1944]

Thomas Mabiletsa: Zulu Piano Medley, No. 2: Part 1, on: Ballantine, Christopher (comp.): Marabi Nights. Historic Recordings (Accompanying CD), University of KwaZulu-Natal Press 2012. [Original c. 1944]