Kwaito

The Bling of Freedom

Kwaito is a contradictory genre. To this day, the stigma of an exclusive orientation towards parties and material values and a lack of political awareness clings to the music and its listeners. In fact, the aesthetics of Kwaito are very affirmative: The beat matching the dance oblivious to its surroundings, the lyrics a repetition of the latest slang catchphrases, and the visual representations – expensive cars and shiny chains – borrowed from the culture of the American rappers. And yet music is always political. It implicitly refers to the realities of life, is embedded in social practices and represents unsatisfied aspirations.

Kwaito has its musical origins in House. Originating in Chicago, this electronic dance music reached South Africa in the late 1980s. House records were at first played by a small group of white DJs and rudimentarily marketed; later, black DJs sold cassettes of compilations of the music to taxi services. There was something fascinating about the tapes: the cassette sleeves were unlabeled and the context was missing. It was clear that the music came from abroad; therefore, it became synonymous with House or simply called International Music.[72]

DJ Tira. Maneta, Rofhiwa: A Look at the History of the Genre through One of its Most Central Figures – DJ Tira. In: The Oral History of Durban Kwaito Music, 2017, © TYRONE BRADLEY / RED BULL CONTENT POOL

For the apartheid period, the emancipatory nimbus of the word international is not to be underestimated: For members of oppressed groups, music from the “outside” has something hopeful and utopian.[73] For house music from overseas another name was created: Kwaito. The etymological origin could be in the Afrikaans expression kwaai, which was used in the sense of “cool” or “hot”.[74] In the upheaval phase of the 1990s, which opened up new opportunities for the acquisition of music equipment, both laymen and trained musicians began to collect International Music, to produce it themselves and to supply it with their own texts – often simultaneously in different languages. Particularly noteworthy were English and Tsotsitaal, both of which were banned at the time of apartheid for black culture, but, in the case of Tsotsitaal, were used in the townships as traffic languages.[75]

This music came to be called “Kwaito”, although “House” still survived as a secondary name. The self-produced pieces differ from the former House in tempo and text. While House usually had about 120bpm, Kwaito had only about 100. Legend has it that a club DJ accidentally played a house record with 33,33rpm instead of 45rpm, this triggering unexpected enthusiasm. More probably, it has to do with the fact that in the 1990s British Speed Garage records were circulating. Because Speed Garage was appreciated among the black youngsters, but the tempo was associated with rock – a genre seen as genuinely “white” music – the records were deliberately played with a lower speed.[76]

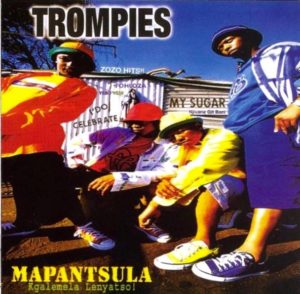

Trompies. Mapantsula, CD cover. Universal Music France Digital Only: Trompies. Mapantsula, 2008, <https://rateyourmusic.com/release/ album/trompies/mapantsula> [24.01.2018]

Kwaito bears a dialectic promise of freedom: It was not the critical comments of journalists that first brought up the collision of the party aesthetic with the flawed reality, and the ideology critique was not needed to convince the supposedly apolitical youth that the Kwaito sparkle was a sham. Rather, this contradiction is inherent in Kwaito: the portrayed carefreeness acts in contrast with reality as an indice for the virtually denied positive freedom in post-apartheid South Africa. And that’s exactly what makes the music political again.

Mandoza: Phunyuka Bamphete, on: ibid.: Phunyuka Bamphete, CCP Records 2005.

Trompies: Celebrate, on: ibid.: Mapantsula, Universal Music 2008.

YouTube Playlist